Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic Retinopathy – Written by Purrven Bajjaj, B Optom, MSc Clinical Optom.

What is diabetic retinopathy?

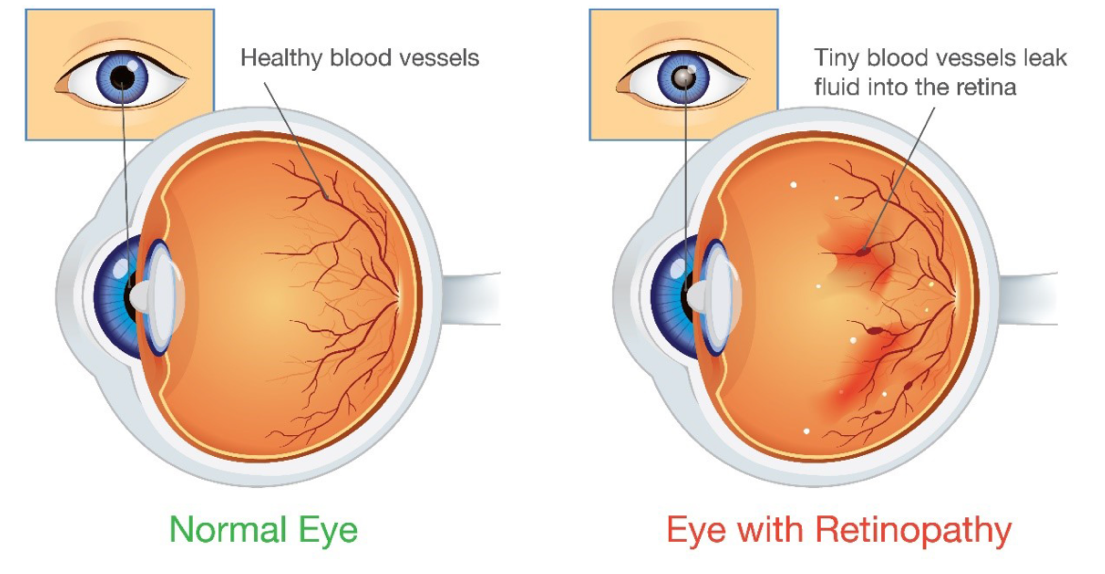

Diabetic retinopathy is an eye disease that can lead to vision loss and blindness in people who have diabetes. It is caused by damage to the blood vessels of the retina (light sensitive tissue at the back of the eye). Diabetic retinopathy may not present with symptoms in the early stages, but detecting it early can help prevent significant vision loss.

Diabetic retinopathy occurs when high blood sugar levels cause changes in the blood vessels of the retina. These blood vessels that nourish the retina can swell and leak fluid, or they can close, therefore stopping blood from passing through. As a result, to make up for these closed blood vessels, the eye grows abnormal new blood vessels on the surface of the retina. These new blood vessels do not develop properly and can leak or bleed easily.

This overview will cover how common is diabetic retinopathy, its global economic impact, its risk factors and types, its common signs and symptoms, how it is diagnosed, as well as its treatment options.

(Source: Campus Eye Center)

How common is diabetic retinopathy?

A global study conducted by the National Eye Institute in 2019 reported that 93 million people in the world live with diabetic retinopathy [1]. The National Eye Institute reported that from 2000 to 2010, the number of people in the United States (US) with diabetic retinopathy increased significantly from 4.06 million to 7.69 million and is projected to nearly double by 2050 to 14.6 million [2].

Diabetic retinopathy is one of the leading causes of blindness in the world. Of the 1.5 billion people affected by blindness in the world, approximately one third is caused by the disease [3].

The economic impact of diabetic retinopathy

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reported that 10% of the annual global health expenditure is spent on diabetes, currently estimated at US$ 760 billion. The economic burden of diabetic retinopathy-related blindness has been estimated at US$ 500 million per year. In the US, a study done in 2004 to analyse the impact of diabetic retinopathy on daily living reported that the cost of screening and treating people with the disease is about US$ 3,200 per person each year [4].

An international organization aimed at helping people with diabetes gain access to insulin issued a report in 2018 finding that 1 in 4 people in the US ration their insulin due to cost-related problems [5]. A US-based analysis reported that if people with diabetic retinopathy lose their ability to work, it would cost the society about US$ 1 million for each patient over a lifetime to receive disability related income recovery. By treating the disease every year, the US economy can save $1.6 billion annually [6].

Risk factors of diabetic retinopathy

Some of the common risk factors of diabetic retinopathy include the following:

Ethnicity

A study done to analyse the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in various ethnic groups worldwide reported that the disease was more prevalent in South Asians, Africans, Hispanics, and in people of tribal descent [5]. The National Eye Institute (US) reported a significant projected increase in people affected with diabetic retinopathy, among which, Hispanic Americans are expected to have the greatest increase from 2010 to 2050, rising almost five-fold, from 1.2 million to 5.3 million [7].

Duration of diabetes

Studies done in Armenia, Beijing, Iran, and Kenya have reported that people who had diabetes for more than 10 years were four times more likely to develop diabetic retinopathy as compared to those with diabetes for less than 10 years [1,6,8,9,10]. In people with diabetes before the age of 30, 1 in 2 develop diabetic retinopathy after 10 years of being diagnosed and 9 in 10 develop the disease after 30 years of being diagnosed [6].

Other diseases

Having high blood pressure or hypertension, in addition to diabetes, increases the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy by three-fold [1,6,11].

Poor control of blood sugar levels

Good control of blood sugar levels, particularly when started early, can prevent or delay the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy [11]. A recent study reported that those with poor blood sugar control were 5 times more likely to develop diabetic retinopathy as compared to the group of people with good blood sugar control [1].

Obesity

Studies conducted in Iran, Beijing, and the US reported that the odds of developing diabetic retinopathy among overweight or obese people were 4 times higher than those with normal body weight [1,8,10]

Types of diabetic retinopathy

People with type 1 or type 2 diabetes are at risk of developing diabetic retinopathy and/or diabetic macula oedema. The following section covers the types of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macula oedema.

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy is the early stage of diabetic retinopathy. In diabetic retinopathy, high blood sugar levels cause changes in the blood vessels of the retina (light sensitive tissue at the back of the eye).

In diabetes, high blood sugar levels are classified into mild, moderate, and severe. Two studies in the US have reported that non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy was present in 25% of people after 5 years of being diagnosed with diabetes, in 60% of people after 10 years, and in 80% of people after 15 years of being diagnosed with diabetes [5,6].

- Mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

In mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, there is a formation of microaneurysms, which are areas of swelling in tiny blood vessels that appear like small air bubbles. Microaneurysms may leak fluid into the retina.

There is a 5% risk that mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy will progress to proliferative diabetic retinopathy [5].

- Moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

As non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy progresses, blood vessels that provide important nourishment to the retina can swell and become weak, losing their ability to transport blood. In moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, tiny blood vessels leak, making the retina swell. Weakened blood vessels disrupt blood flow in the veins of the retina. When blood vessels constrict (become smaller) and dilate (become bigger) irregularly, it is referred to as venous beading. Blood vessels in the retina can close off and this is referred to as macula ischemia. This happens when blood cannot reach the macula. As a result, tiny particles called exudates can form in the retina.

There is a 27% risk that moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy will progress to proliferative diabetic retinopathy within 1 year of diagnosis [6].

- Severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

In severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, more blood vessels become affected and swell, leading to a loss of blood flow to the retina. In response to this, the retina starts to secrete chemicals for new blood vessels to grow.

People with severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy have a 52% risk of developing proliferative diabetic retinopathy within 1 year of diagnosis [12].

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy is a more advanced form of diabetic retinopathy. Problems in the blood circulation of the retina deprive the retina of oxygen. In an attempt to fix this, new abnormal blood vessels can grow in the retina and into the vitreous (transparent gel like fluid that fills the back of the eye). This is called neovascularization.

Diabetic macula oedema or clinically significant macula oedema

Diabetic macula oedema, also known as clinically significant macula oedema, can occur at any stage of diabetic retinopathy and causes damage to the blood vessels in the retina. The damaged blood vessels can leak fluid that may lead to swelling of the surrounding tissue in the retina, including the macula. The macula is an area of the retina responsible for clear and sharp vision, as well as colour vision, and this swelling in the macula may lead to distorted vision. When the macula swells in people with diabetes, it is called diabetic macula oedema.

Approximately 8 in 100 people affected by diabetic retinopathy have diabetic macula oedema [13,14]. A study done over 14 years to analyze diabetic macula oedema in people with diabetes reported that the number of people with type 2 diabetes affected by diabetic macula oedema was more than double as compared to diabetic macula oedema in people with type 1 diabetes [15].

What are the common signs and symptoms of diabetic retinopathy?

Diabetic retinopathy progresses through 4 stages, mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. In the early stages, diabetic retinopathy often does not have any symptoms, and the disease can go undetected until it affects vision [15]. Some of the common signs and symptoms of diabetic retinopathy include:

- Floaters (spots or dark strings floating in field of vision)

- Blurred or patchy vision

- Sudden vision loss

If you experience any of these signs and symptoms, schedule an appointment with an eye health professional to get your eyes checked. It is also important to note that the development of eye conditions may even start before symptoms appear, which makes going for regular and timely eye checks that much more essential.

Complications of diabetic retinopathy

If not detected and treated early, diabetic retinopathy may lead to other complications, which include the following:

Vitreous haemorrhage

In proliferative diabetic retinopathy, new blood vessels grow in an attempt to fix the problems with blood circulation in the retina. These new fragile blood vessels may leak blood into the vitreous, affecting vision. If these blood vessels bleed a little, it might be seen as a few dark floaters. If these blood vessels bleed a lot, it can even block vision.

Retinal detachment

The abnormal blood vessels associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy stimulate the growth of scar tissue, which can pull the retina away from the back of the eye and cause retinal detachment. This can appear as spots floating in our vision or flashes of light.

Glaucoma

New abnormal blood vessels associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy can grow in the iris (coloured tissue at the front of the eye) and interfere with the normal drainage of fluid in the eye. This can cause pressure in the eye to build up and can damage the optic nerve (cable that sends all visual messages to the brain, producing vision), which may lead to glaucoma.

How is diabetic retinopathy diagnosed?

Diabetic retinopathy is diagnosed by trained eye health professionals through a comprehensive eye check. To allow for better and wider examination of the retina, eye drops are often used to dilate or widen the pupil (dark spot in the centre of the eye) and the eye professional will then do a dilated eye exam. Dilation eye drops take about 30 minutes to effectively dilate the pupil for examination and will cause a temporary blurring of vision that resolves after about 4 to 6 hours.

When the eye health professional suspects that diabetic retinopathy has progressed to proliferative diabetic retinopathy or diabetic macula oedema, a fluorescein angiography is done to see what is happening with the blood circulation in the retina. A yellow dye called fluorescein is injected into a vein in the arm and the dye travels through blood vessels. A special equipment is then used to take photos of the retina as the dye travels through the blood vessels. The images can identify new, closed, or leaking blood vessels.

An optical coherence tomography (OCT) is another machine often used when doing eye examinations on people with diabetes. It scans the retina and provides detailed images of its thickness, allowing identification and measurement of the swelling, if any, on the macula. OCT images are also used to monitor the effectiveness of the treatment.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends the following frequency for comprehensive eye checks [5,16]:

- People with type 1 diabetes should have a comprehensive dilated eye check within 5 years of disease onset

- People with type 2 diabetes should have a comprehensive dilated eye check at the time of diagnosis and yearly thereafter

- Women who were previously diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes should have a comprehensive dilated eye check before becoming pregnant or within the first 3 months of pregnancy

- If there is no evidence of diabetic retinopathy on the initial eye examination, ADA recommends that people with diabetes get comprehensive dilated eye checks at least once every 2 years

- If diabetic retinopathy is present on the initial eye examination, based on the type and severity of the disease, the eye health professional will recommend how often an eye check is required

How is diabetic retinopathy treated?

Treatment for diabetic retinopathy depends on the type and severity of the disease. In mild or moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, treatment is not usually required, and eye health professionals will closely monitor the disease to determine when treatment is needed. Good control of blood sugar levels is important in slowing the progression of diabetic retinopathy and the eye health professional may recommend a consultation with a diabetes specialist (endocrinologist) for advice.

In severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and diabetic macula oedema, it is important to start treatment as early as possible. While treatment may not undo the existing damage to vision, treatment can stop vision from getting worse. Even after treatment, regular comprehensive dilated eye checks are required. The treatment options for diabetic retinopathy include:

Injecting medications into the eye

Medications called anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) inhibitors are injected into the vitreous (transparent gel like fluid that fills the back of the eye) to help stop the growth of new blood vessels and decrease the build-up of fluid. These injections are injected using topical anaesthesia and can cause mild discomfort. Steroid injections are another option to reduce macula swelling.

Injections are usually given once a month to begin with and the ophthalmologist (eye doctor) will recommend how many injections are needed subsequently.

Laser treatment

In some cases, laser treatments need to be administered in addition to anti-VEGF injections. This can reduce the swelling of the retina and shrink the blood vessels, as well as prevent them from growing again. In some cases, more than one session is needed.

Photocoagulation or focal laser treatment can stop or slow the leakage of blood and fluid in the eye. Photocoagulation is usually done in an ophthalmologist’s (eye doctor) office or clinic in a single session.

Panretinal photocoagulation is another laser treatment that is also known as scatter laser treatment. This treatment aims to shrink the abnormal blood vessels on the retina. Areas of the retina that are located away from the macula are treated with scattered laser burns, causing the abnormal new blood vessels to shrink and scar. Panretinal photocoagulation is usually done in an Oophthalmologist’s (eye doctor) office or clinic in two or more sessions.

Vitrectomy

In proliferative diabetic retinopathy, abnormal new blood vessels can leak into the vitreous (transparent gel like fluid that fills the back of the eye), causing a haemorrhage. When this occurs and cannot resolve on its own, a vitrectomy is required. A tiny incision is made in the eye to remove blood from the vitreous and scar tissue tugging on the retina. A vitrectomy is done in a surgery centre or hospital using local or general anaesthesia.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References

- “National Eye Institute”, Nov 2020, Available: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/outreach-campaigns-and-resources/eye-health-data-and-statistics/diabetic-retinopathy-data-and-statistics. [Accessed: 05 Aug 2021]

- “National Eye Institute”, Nov 2020, Available: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/outreach-campaigns-and-resources/eye-health-data-and-statistics/diabetic-retinopathy-data-and-statistics. [Accessed: 05 Aug 2021]

- S. R. Flaxman et al., “Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis.“, Lancet Glob Health, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 1221-34, 2017, doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5.

- E. L. Lamoureux, J. B. Hassell, J. E. Keeffe. “The impact of diabetic retinopathy on participation in daily living.”, Arch Ophthalmol, vol. 122, no. 2, pp. 84-88, 2004, doi:10.1001/archopht.122.1.84

- R. Klein et al.,. “The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years.”, Arch Ophthalmol, vol. 102, no. 4, pp. 520-6, 1984.

- “The Silver Book”, Alliance for ageing and research, [Online], Available: https://www.silverbook.org/fact/dr-treatment-savings-in-the-us/. [Accessed: 05 Aug 2021]

- “National Eye Institute”, Nov 2020, Available: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/outreach-campaigns-and-resources/eye-health-data-and-statistics/diabetic-retinopathy-data-and-statistics. [Accessed: 05 Aug 2021]

- W. Mathenge et al., “Prevalence and correlates of diabetic retinopathy in a population-based survey of older people in Nakuru, Kenya.”, Ophthalmic Epidemiol, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 169-77, 2014, doi:10.3109/09286586.2014.903982

- D. Dabelea et al., “Association of type 1 diabetes vs type 2 diabetes diagnosed during childhood and adolescence with complications during teenage years and young adulthood.”, JAMA, vol. 317, no. 8, pp. 825-35, 2017, doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0686

- J J Kanski, Clinical Ophthalmology A systematic approach, 7th ed. Windsor, UK: Elselver Saunders, 2011, pp. 534-543

- P J. Chua, C. Xin, Y. Lim, T. Y. Wong. “Diabetic retinopathy in the asia-pacific.”, Asia Pacific J Ophthalmol, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 3-16, 2018.

- “Prediabetes-Your chance to prevent type 2 diabetes”, Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Jun 11 2020, [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/prediabetes.html#:~:text=Approximately%2088%20million%20American%20adults,%2C%20heart%20disease%2C%20and%20stroke.[Accessed: 05 Aug 2021]

- N. Hancho, J. Kirigia, K. O. Claude, IDF Diabetes Atlas, vol. 8, International Diabetes Fedration, 2017, pp. 1-150.

- R. Lee, T. Y. Wong, C. Sabanayagam, “Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema and related vision loss.”. Eye Vis, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 1-25, 2015, doi:10.1186/s40662-015-0026-2.

- R. A. Pedro, “Managing diabetic macular edema: The leading cause of diabetes blindness.”, World J Diabetes, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 98-104, Jun 11 2015, doi: 10.4239/wjd.v2.i6.98

- B.E Klein. “Overview of epidemiologic studies of diabetic retinopathy.”, Ophthalmic Epidemiol, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 179-83, 2007.

Tools Designed for Healthier Eyes

Explore our specifically designed products and services backed by eye health professionals to help keep your children safe online and their eyes healthy.