Giant Cell Arteritis

Giant cell arteritis – Written by Dr. Ali Dirani, MD, MSc, MPH and Eunice Linh You, MD, Ophthalmology Resident

What is giant cell arteritis?

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), also known as temporal arteritis or Horton’s arteritis, is the inflammation of the lining of the medium and large sized arteries in the body. GCA is part of a spectrum of diseases that includes polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), which is an inflammation of the large muscle groups such as the shoulders and hips. GCA is a medical emergency and if not promptly diagnosed and treated, may lead to irreversible vision loss in both eyes as well as potentially be life-threatening [1].

The following sections will briefly outline how common is GCA, who is affected by GCA, how GCA develops, its signs and symptoms, as well as some insights into its treatment strategies.

How common is giant cell arteritis?

GCA is the most common form of systemic vasculitis (inflammation of blood vessel walls) but is still quite rare. Studies from Canada [3], the United Kingdom [4], the United States [5] and Scandinavian countries [6] suggest that there are between 15 and 25 cases of GCA per 100,000 persons over the age of 50 years old.

Who is affected by giant cell arteritis?

GCA is a disease of the elderly, with an average affected age of 75 years old. The risk of GCA is almost non-existent in those under the age of 50 years old. The risk also increases with age, with those in the 9th decade of life having a 20-fold increased risk compared to those in the 6th decade of life. Women are twice as likely to be affected compared to men [3]. White patients, especially those from European and Scandinavian ancestry, are more commonly affected by GCA than those from Asian and Black Caribbean or African descent [7, 8].

How does giant cell arteritis develop?

While there has been significant progress in our understanding of GCA, the exact causes of GCA remains unknown. An abnormal response of the immune system to injury of the blood vessels, such as from a previous trauma or infection, may play a role. The body produces an inappropriate inflammatory response with giant cell formation that can be seen on examination with a microscope [2].

What are the common signs and symptoms of giant cell arteritis?

- New, persistent headache usually around the temple

- Tenderness of the scalp

- Pain or tiredness in the jaw after brief periods of chewing

- Unexplained flu-like symptoms including fatigue, unintended weight loss and fever

- Pain or stiffness in the neck, shoulders, or hip

- Sudden, permanent vision loss or other vision troubles

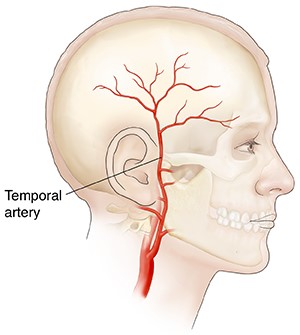

Headaches are present in 70-80% of people with GCA. It is usually a one-sided, severe, throbbing headache around the temporal area. Patients may also notice a prominent blood vessel near their temples. Scalp tenderness tends to occur a few weeks before the headaches and may make it painful for patients to shave or brush their hair.

Jaw claudication, which is pain or tiredness in the jaw after a brief period of chewing, can occur in 40% of GCA cases. Jaw pain points toward an abnormality in the blood flow from the temporal artery to the muscles of the jaw and is associated with a high likelihood of having GCA [9].

Most patients describe non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, unintended weight loss, and loss of appetite. Fever is present in up to 40% of cases [2, 9].

GCA is also part of a spectrum of diseases that includes polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), an inflammation of the large muscle groups such as the shoulders and hips. Symptoms of PMR include muscle aching and stiffness that is worse in the morning and usually centred around the large muscles of the body, such as the shoulders and the hips. Patients may have trouble raising their arms to comb their hair or getting up from a chair or a car [9].

If you experience any of these signs and symptoms, schedule an appointment with an eye health professional to get your eyes checked. It is also important to note that the development of eye conditions may even start before symptoms appear, which makes going for regular and timely eye checks that much more essential.

How does giant cell arteritis affect vision?

One of the most feared complications of GCA is irreversible and permanent vision loss. Almost two-thirds of patients with GCA present with visual symptoms and up to one in three will suffer from irreversible vision loss [10]. Patients often describe loss of a visual field, like a curtain covering a part of their vision in one eye. In up to 20-62% of patients, both eyes are affected, whether at the same time or one eye after the other [11].

Although the vision loss is often irreversible, one of the most important reasons for having prompt diagnosis and treatment is to prevent vision loss in the other eye [2].

What are the other complications associated with giant cell arteritis?

Uncommonly, patients may also develop aneurysms of the aorta, the large artery in the chest and abdomen. Aneurysms are bulges in areas of weakened blood vessels that may burst and cause life-threatening internal bleeding. As a result, patients with GCA are often followed with annual imaging of their large arteries [12].

How is giant cell arteritis diagnosed?

The diagnosis of GCA is often made by ophthalmologists based on clinical presentation and investigative test results. Blood tests measuring for erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are typically the first diagnostic test. ESR and CRP are markers of inflammation and are often elevated in GCA patients. Having an elevation of both markers is associated with high odds of having the disease while normal values for both markers is reassuring.

The best test for GCA is a biopsy of the temporal artery. A biopsy must be done with as minimal delay in every patient with a suspicion of GCA. This test is very sensitive and can detect 90-95% of cases. This means that only about 5-10% of patients with a negative biopsy may turn out later to have GCA.

Even in patients who have already started corticosteroid treatment, the biopsy may still provide useful information if done within 2 weeks of treatment [2]. The steroid treatment should not be delayed for the biopsy. In certain cases, there may be imaging tests to evaluate the vessels in the body. Ultrasonography with color doppler, which does not involve radiation, is an evolving technique for GCA diagnosis although it is highly user dependent [2].

What is a temporal artery biopsy?

A temporal artery biopsy is a procedure to remove a section of the temporal artery for testing. The sample is sent to a lab to be closely examined for signs of inflammation suggestive of GCA.

The doctor will first numb the area. An incision (cut) is made near the hairline and the temporal artery is identified. A small section of the artery is removed and the ends of the artery are tied off. The incision is closed with stitches and antibiotic medications are prescribed to reduce risk of infection. Usually, the incision heals with a thin scar [13].

How does an eye health professional confirm that you have giant cell arteritis?

A detailed eye examination including checking vision and the pupils (dark spot at the centre of the eye) provides information on the state of the optic nerve (structure that sends all visual signals to the brain, allowing vision). A dilated fundus examination is completed to look for evidence of ischaemia (inadequate blood supply) or inflammation of the optic nerve head. Patients may also undergo a visual field examination as well as other imaging tests of the layers and vessels of the back of the eye [2].

What are the treatment options for giant cell arteritis?

High dose steroid therapy is the main treatment option for GCA and should be started immediately. The steroids are continued for several weeks before slowly lowering the dose over several months and even years to prevent the disease from relapsing.

Symptoms such as headaches, jaw pain, and muscle stiffness often ease quickly with treatment and the results of the blood tests will eventually normalize. There are new studies looking at the use of a drug called tocilizumab as an alternative to high steroid therapy. Tocilizumab has been recently approved by the FDA and is given as an injection at the doctor’s office. However, patients must be evaluated prior to injection as not all patients are good candidates for this medication [14, 15].

What are some side effects of the corticosteroid treatment?

Steroids may cause weakening of the bones and increase the risk of fractures. Patients are often treated with vitamin D and calcium as well other prescription medications like bisphosphonates for prevention of bone loss [16]. Other side effects may include mood changes, fatigue, poor sleep, weight gain, and a lower resistance to infections [14].

Due to these side effects, patients must be carefully monitored by their doctor.

Vision and giant cell arteritis

Unfortunately, the vision loss caused by GCA is often severe and permanent, although some degree of improvement does occur in a small number of patients. In one study, less than 40% of patients had a better vision than 20/200. This means that when reading the Snellen Chart at a fixed distance, less than 40% of patients were able to see letters at 20 ft (around 6 m) that a person with normal vision could see at 200 ft (around 60 m) [11]. However, treatment is usually effective at preventing vision loss in the other eye.

Can I prevent giant cell arteritis?

There is no prevention for GCA. We can only prevent the disease from affecting vision in the other eye by treating the inflammation and monitoring for any signs of relapse during treatment.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, include but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health care provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References

- H. S. Lyons, V. Quick, A. J. Sinclair, S. Nagaraju, and S. P. Mollan, “A new era for giant cell arteritis,” Eye, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 1013-1026, 2020/06/01 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41433-019-0608-7.

- M. A. Ameer, R. J. Peterfy, P. Bansal, and B. Khazaeni, “Temporal Arteritis,” in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2021, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2021.

- L. Barra et al., “Incidence and prevalence of giant cell arteritis in Ontario, Canada,” Rheumatology, vol. 59, no. 11, pp. 3250-3258, 2020, doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa095.

- L. Smeeth, C. Cook, and A. J. Hall, “Incidence of diagnosed polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis in the United Kingdom, 1990-2001,” (in eng), Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 65, no. 8, pp. 1093-8, Aug 2006, doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.046912.

- T. A. Kermani et al., “Increase in age at onset of giant cell arteritis: a population-based study,” (in eng), Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 780-1, Apr 2010, doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.111005.

- O. Baldursson, K. Steinsson, J. Björnsson, and J. T. Lie, “Giant cell arteritis in Iceland. An epidemiologic and histopathologic analysis,” (in eng), Arthritis Rheum, vol. 37, no. 7, pp. 1007-12, Jul 1994, doi: 10.1002/art.1780370705.

- C. A. Smith, W. J. Fidler, and R. S. Pinals, “The epidemiology of giant cell arteritis. Report of a ten-year study in Shelby County, Tennessee,” (in eng), Arthritis Rheum, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 1214-9, Oct 1983, doi: 10.1002/art.1780261007.

- R. D. Wigley et al., “Rheumatic diseases in China: ILAR-China study comparing the prevalence of rheumatic symptoms in northern and southern rural populations,” (in eng), J Rheumatol, vol. 21, no. 8, pp. 1484-90, Aug 1994.

- A. Winkler and D. True, “Giant Cell Arteritis: 2018 Review,” (in eng), Mo Med, vol. 115, no. 5, pp. 468-470, Sep-Oct 2018. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30385998 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6205276/.

- L. Donaldson and E. Margolin, “Vision loss in giant cell arteritis,” (in eng), Pract Neurol, Jul 8 2021, doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2021-002972.

- I. Vodopivec and J. F. Rizzo, III, “Ophthalmic manifestations of giant cell arteritis,” Rheumatology, vol. 57, no. suppl_2, pp. ii63-ii72, 2018, doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex428.

- H. Kwon, Y. Han, D. H. Son, Y.-P. Cho, and T.-W. Kwon, “Abdominal aortic aneurysm in giant cell arteritis,” (in eng), Ann Surg Treat Res, vol. 89, no. 4, pp. 224-227, 2015, doi: 10.4174/astr.2015.89.4.224.

- E. Chase, B. C. Patel, and M. L. Ramsey, “Temporal Artery Biopsy,” in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2021, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2021.

- C. Ponte, A. F. Rodrigues, L. O’Neill, and R. A. Luqmani, “Giant cell arteritis: Current treatment and management,” (in eng), World J Clin Cases, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 484-494, 2015, doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i6.484.

- T. Ness, T. A. Bley, W. A. Schmidt, and P. Lamprecht, “The diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis,” (in eng), Dtsch Arztebl Int, vol. 110, no. 21, pp. 376-386, 2013, doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0376.

- Z. Paskins et al., “Risk of fracture among patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a population-based study,” BMC Medicine, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 4, 2018/01/10 2018, doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0987-1.

Tools Designed for Healthier Eyes

Explore our specifically designed products and services backed by eye health professionals to help keep your children safe online and their eyes healthy.