Vitreous detachment

Vitreous detachment – Written by Dr. Ali Dirani, MD, MSc, MPH and Mélanie Hébert, MD, MSc.

What is vitreous detachment?

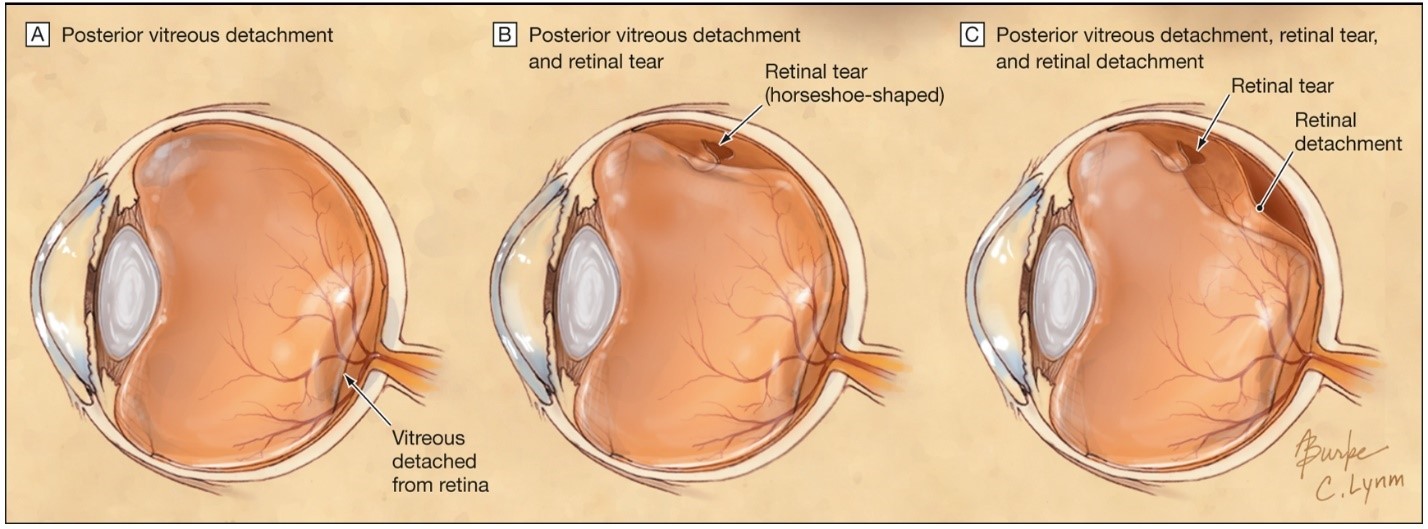

The eye is filled with a clear, jelly-like substance called the vitreous. The vitreous starts off attached to the retina, which is a layer at the back of the eye that transmits light information to our brain, allowing us to see. With time and age, the vitreous starts to liquify and gradually shrink. This shrinking process may cause the vitreous to detach from the retina, leading to vitreous detachment or posterior vitreous detachment. This happens as people grow older and is different from retinal detachment (see Figure 1).

In most people, vitreous detachment occurs without consequence. However, in some people, the vitreous can tug harder on the retina and cause it to break the lining of the retina, causing a retinal break or tear. This is more likely in people with myopia or those who have received a hit to the eye [1]. The vitreous can also tug on a blood vessel in the retina, which can cause a bleed in the eye called a vitreous haemorrhage.

When a retinal tear happens, the liquified vitreous can slide behind the retina and like a tapestry, the retina can detach from the wall of the eye. This is then called a retinal detachment which causes vision loss.

How many people are affected by vitreous detachment?

Vitreous detachment usually occurs in older people. Most people who see an eye health professional for vitreous detachment are between 45 and 65 years of age [3]. By the age of 80 to 89 years, more than 4 in 5 people would have had a vitreous detachment [4]. However, people who have myopia (when the eye is longer and the retina is more stretched out), this can happen at a younger age [5]. They are also at a higher risk of having complications such as retinal tears and retinal detachments [6]. Vitreous detachment can also occur due to trauma from getting hit in the eye [3] or after an eye surgery [7]. Approximately 8% to 22% of patients who have a vitreous detachment will be found to also have a retinal tear [8].

What are the common signs and symptoms of vitreous detachment?

People suffering from vitreous detachment often develop flashes of light like photographs or floaters like little flies in their vision. The flashes are produced when the vitreous tugs on the retina as it detaches, sending electrical signals to the brain which is then interpreted as flashes. The floaters occur as the vitreous liquifies and shrinks, producing debris in the eye that can cast shadows. These floaters can also be a sign of vitreous haemorrhage when the vitreous tugs on a blood vessel on the retina, causing it to bleed. This can also lead to blurry vision.

The serious complication of vitreous detachment is retinal detachment. In retinal detachment, people can have sudden vision loss or lose a part of their vision, like a curtain of darkness gradually falling on their vision. With this symptom, people should consult an eye health professional urgently or go to the closest emergency room to be treated quickly.

If you experience any of these signs and symptoms, schedule an appointment with an eye health professional to get your eyes checked. It is also important to note that the development of eye conditions may even start before symptoms appear, which makes going for regular and timely eye checks that much more essential.

How is vitreous detachment diagnosed?

When patients have flashes of light or floaters, an eye health professional will do a full eye exam, including a dilated fundus exam. This is when the pupil, which is the dark centre of the eye, is increased in size using eyedrops to better see the retina at the back of the eye. Sometimes, the eye health professional can see a ring called a Weiss ring floating in the vitreous, which indicates that the vitreous has completely detached. Vitreous detachments can occasionally be seen with specialized scans of the retina, called optical coherence tomography (OCT) as well.

The most important part of the exam is to verify the entire retina to make sure that the vitreous is not tugged hard enough on the retina to cause a retinal tear or a retinal detachment. To verify this, the eye health professional will shine a light into your eye to see the back of your eye and may use different types of lenses to magnify the retina to see it better.

Different types of instruments can be used to see the retina (see Figure 2). If there is a vitreous haemorrhage, it can be more difficult to examine the entire retina, so an ultrasound machine called a B-scan ultrasound can be used to check whether the retina is detached, like how ultrasounds are done in pregnant people.

Is there a treatment for vitreous detachment?

There is currently no treatment for vitreous detachment. When it is not complicated by retinal tears or retinal detachment, there is generally no serious consequence to it. The floaters stay in the eye forever, but they will generally disappear from your vision gradually as the brain becomes used to them. However, people may keep seeing them from time to time.

If the vitreous is tugged on the retina and causes a tear, an ophthalmologist who is a medical doctor specialized in eye health can conduct a short procedure called a laser retinopexy. This procedure involves using a laser to solidify the retina around the tear to prevent the liquified vitreous from going behind the tear and detaching the retina.

If the retina is detached, an ophthalmologist specialized in vitreous and retinal surgeries will offer the patient an operation to reattach the retina.

Since vitreous detachment is a dynamic process [1], it may not have completely detached by the time an eye health professional examines the entire retina. This means that some people can have retinal tears or retinal detachments that appear later [12]. It is therefore important to have a follow-up examination with an eye health professional within the few months after the symptoms appear. It is also important to come back sooner if the flashes worsen, if there are multiple new floaters, or if there is a curtain of darkness that appears.

Can vitreous detachment be prevented?

Nothing specific can be done to prevent vitreous detachment as the process normally occurs with age. That said, since it can be caused by traumas, basic eye protection with protective eyewear or goggles can help prevent the eyes from getting hit by objects. This is particularly important at certain workplaces, when doing construction, or playing sports.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References

- C. J. Flaxel et al., “Posterior Vitreous Detachment, Retinal Breaks, and Lattice Degeneration Preferred Practice Pattern®,” Ophthalmology, vol. 127, no. 1, pp. P146–P181, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.027.

- H. Hollands, D. Johnson, A. C. Brox, D. Almeida, D. L. Simel, and S. Sharma, “Acute-Onset Floaters and Flashes: Is This Patient at Risk for Retinal Detachment?,” JAMA, vol. 302, no. 20, pp. 2243–2249, Nov. 2009, doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1714.

- M. P. Snead, D. R. J. Snead, S. James, and A. J. Richards, “Clinicopathological changes at the vitreoretinal junction: posterior vitreous detachment,” Eye, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 1257–1262, Oct. 2008, doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.41.

- T. Hikichi et al., “Comparison of the prevalence of posterior vitreous detachment in whites and Japanese,” Ophthalmic Surg, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 39–43, Feb. 1995.

- K. Hayashi, S. Manabe, A. Hirata, and K. Yoshimura, “Posterior Vitreous Detachment in Highly Myopic Patients,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 61, no. 4, p. 33, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.4.33.

- The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group, “Risk Factors for Idiopathic Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment,” American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 137, no. 7, pp. 749–757, Apr. 1993, doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116735.

- A. M. Coppé and G. Lapucci, “Posterior vitreous detachment and retinal detachment following cataract extraction,” Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 239–242, May 2008, doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282fc9c4a.

- R. E. Coffee, A. C. Westfall, G. H. Davis, W. F. Mieler, and E. R. Holz, “Symptomatic Posterior Vitreous Detachment and the Incidence of Delayed Retinal Breaks: Case Series and Meta-analysis,” American Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 144, no. 3, pp. 409-413.e1, Sep. 2007, doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.05.002.

- Amy Dinardo and Philip Walling, “The Lost Arts of Optometry, Part Three: Going Back to Gonio,” Review of Optometry. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/the-lost-arts-of-optometry-part-three-going-back-to-gonio-44408 (accessed Aug. 25, 2021).

- Christopher Nathaniel Roybal, “Indirect Ophthalmoscopy 101,” American Academy of Ophthalmology, May 15, 2017. https://www.aao.org/young-ophthalmologists/yo-info/article/indirect-ophthalmoscopy-101 (accessed Aug. 25, 2021).

- Retina Macula Institute, “Ocular Ultrasound,” Retina Macula Institute. https://retinamaculainstitute.com/ocular-ultrasound (accessed Aug. 25, 2021).

- J. H. Uhr et al., “Delayed Retinal Breaks and Detachments after Acute Posterior Vitreous Detachment,” Ophthalmology, vol. 127, no. 4, pp. 516–522, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.10.020.

Tools Designed for Healthier Eyes

Explore our specifically designed products and services backed by eye health professionals to help keep your children safe online and their eyes healthy.