Retinitis Pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa – Written by Associate Professor Lauren Ayton, B Optom, PhD, FAAO, FACO.

What is retinitis pigmentosa (RP)?

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the collective term for a group of inherited eye diseases, which cause progressive vision loss. RP causes degeneration to the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. In particular, RP damages the photoreceptors, which are the cells that transform light entering into the eye into visual signals.

There are two forms of photoreceptors – cones and rods. Cones are responsible for vision in light conditions such as daytime and colour vision, while rods work more in dim lighting conditions. Rod photoreceptors are located mainly in towards the edges of the retina, and they play a large role in our peripheral, or side, vision.

RP is also known as rod-cone dystrophy, as it causes damage to the rod photoreceptors first, followed by the cone photoreceptors. This means that the initial symptoms are often difficulties with night vision and loss of peripheral vision.

This overview will cover how common RP is, its causes, how it is diagnosed, the genetic testing for RP, its common signs and symptoms, how it can be treated, as well as what the future holds for people with RP.

How common is retinitis pigmentosa?

It is estimated that around one in 3,000 people have RP, but this does vary significantly around the world. Some countries, including India, China and Scandinavian countries, tend to have higher levels of RP in their communities – up to one in 1,000 people [1,2]. Globally, over 1.5 million people have a form of RP [3].

RP is one form of inherited retinal disease (IRD). The definition of IRD also includes macular dystrophies, choroideremia, and other genetic retinal disease. Overall, IRD is now the most common cause of legal blindness in working-aged adults [4,5]. So, while each individual subtype of IRD is rare, as a whole these conditions have a significant impact.

Approximately 20 to 30% of people with RP have an associated systemic syndrome, which affects other parts of their body [6]. The most common is Usher syndrome, which causes both hearing loss and RP. There are three categories of Usher syndrome, depending on the type and severity of the symptoms. Usher syndrome Types 1 and 2 account for around 10 per cent of children who are born deaf [7].

What causes retinitis pigmentosa?

RP is caused by more than 100 different genes [8], which can be inherited in various ways.

- Autosomal recessive: This is the most common way that RP is inherited. In autosomal recessive disease, both parents have one copy of the gene mutation. There is a 25% chance that their child will inherit both of these genes and develop RP.

- Autosomal dominant: In this case, an affected parent with the gene mutation (who will usually show signs of RP) passes the gene on to their child. In this situation, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the gene and developing RP.

- X-linked: This is a rarer form of RP, where the gene mutation is passed down from the mother on the X-chromosome. In this case, the mother is normally unaware that she is a “carrier” of the condition. X-linked RP is seen in males, and each son of a carrier has a 50% chance of inheriting the gene and developing RP.

How is retinitis pigmentosa diagnosed?

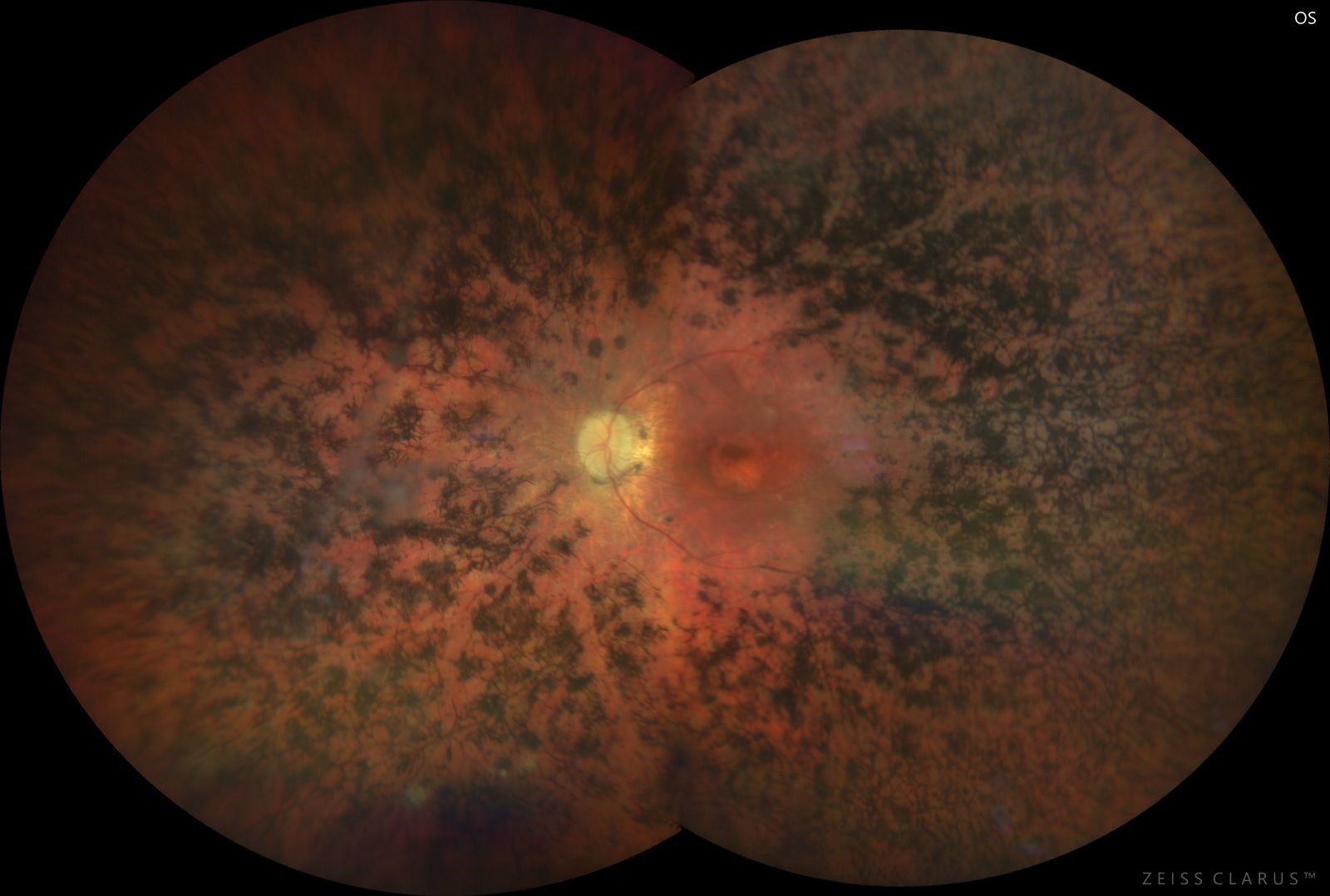

RP is diagnosed by an ophthalmologist through a range of eye tests. Many of these tests are standard clinical care, including measurement of vision, assessment of the back of the eye and retina, and taking photos and scans of the eye. The retina shows characteristic changes in RP, including areas of black pigmentation (which is where the “pigmentosa” in the name comes from). Figure 1 shows an example of a photo of the retina in a person with RP.

Specialised tests are often needed to confirm diagnosis of RP. One example is an electroretinogram, which is a test that records the electrical activity of the retina in response to light. It is similar to an electrocardiogram (ECG) test and requires specialised equipment and technicians.

Another common clinical test for RP is a visual field test, where you click a button to let the examiner know if you can see lights in your peripheral vision. As well as being a useful test for diagnosing and monitoring RP, visual field tests are a good way for people to get an understanding of areas where their vision is not as good. This can help them be more careful and avoid falls.

Often diagnosis of RP requires referral to a specialist ophthalmologist, who is an expert in inherited retinal diseases.

Genetic testing for retinitis pigmentosa

Conclusive diagnosis of RP requires genetic testing, which usually (but not always) can identify the gene mutation that has caused the particular subtype of RP.

Genetic testing can be accessed through ophthalmologists and clinical genetics services (both public and private). It is also important to undertake genetic counselling, which will provide an explanation of the results, and what they mean for an individual. This is particularly important for people who are family planning.

What are the common signs and symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa?

As RP can be caused by more than 100 different genes, the clinical presentation and disease progression can be very different. Some people are diagnosed with RP as very young children. This is particularly common with a subtype of RP called Leber Congenital Amaurosis. In other cases, people do not find out they have RP until much later in life.

Similarly, the rate of vision loss is variable between the different subtypes of RP. Some people have rapid changes in their vision, while others experience a very slow decline in their sight.

In general, the early symptoms of RP are:

- Poor night vision

- Problems seeing things in dim lighting

- Loss of peripheral (side) vision

- Trouble noticing objects in the peripheral vision, which can lead to tripping, stumbling, or clumsiness

As RP progresses, and more rod photoreceptors are affected, people will lose more of their peripheral vision. This can lead to “tunnel vision”, where people can only see in the very centre of their visual field. In less than 0.5% of cases, the late stages of RP can result in total vision loss (“black blindness”) [9].

RP is also associated with other eye conditions, such as a higher risk of cataracts or macular oedema (swelling of central region of the retina). These conditions can usually be effectively treated with cataract surgery, or drugs to reduce the macular oedema.

If you experience any of these signs and symptoms, schedule an appointment with an eye health professional to get your eyes checked. It is also important to note that the development of eye conditions may even start before symptoms appear, which makes going for regular and timely eye checks that much more essential.

How is retinitis pigmentosa treated?

Until recently, there were no effective treatments for RP. This has recently changed, with the approval of a gene therapy treatment for a form of RP called Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA).

Gene therapy

LCA is a severe form of RP which starts in early childhood and affects around 1% of people with RP [10].

The gene therapy, voretigene neparvovec-rzyl (Luxturna®), is suitable for people who have a specific mutation in a gene called RPE65. The treatment is a once-off injection into the eye, and has been shown to slow the disease in most cases [10]. In some cases, the treatment can even restore some degree of vision.

To determine whether a person has a form of RP that could benefit from this new gene therapy, they need to undergo genetic testing.

Vitamins and supplements

Other medical treatments for RP have been trialled, but have not shown strong evidence for use [11]. These include vitamins and nutritional supplements, such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and lutein. Advice on diet and RP can be provided by your eyecare practitioner. It is important to seek medical advice, as some vitamins might be harmful for certain forms of inherited retinal disease.

Mobility aids

There are also a number of useful aids that can help people with low vision from RP. Mobility aids include long canes, guide dogs, and electronic wayfinders. Information access can be aided with smartphones, electronic magnifiers, and audio devices. Low vision therapists, orientation and mobility instructors, and occupational therapists can greatly assist with these aids, and with other strategies to optimise people’s vision.

Vision prosthesis (bionic eyes)

Finally, people who have lost significant vision from RP may be eligible for a vision prosthesis, or “bionic eye”. These are electronic devices which are implanted into the eye or brain, and which can restore some functional vision to the recipient.

Can I reduce the risk of developing retinitis pigmentosa?

There are no known ways to reduce the risk of developing RP.

What does the future hold for people with retinitis pigmentosa?

There are many research programs and clinical trials underway to discover new treatments for RP. These include gene therapy, stem cells, anti-oxidant medications and neuroprotective drugs. Given the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of a gene therapy for RP in 2017, it is anticipated that other gene therapies will follow in the near future.

Support for people with RP is available through many resources, including Retina International. In addition, your eyecare practitioner will be able to keep you updated on the latest advances in research.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, include but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health care provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References

- Nangia V, Jonas JB, Khare A, Sinha A. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in India: the Central India Eye and Medical Study. Acta Ophthalmol 2012;90(8):e649-50.

- Xu L, Hu L, Ma K, et al. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in urban and rural adult Chinese: The Beijing Eye Study. Eur J Ophthalmol 2006;16(6):865-6.

- Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006;368(9549):1795-809.

- Heath Jeffery RC, Mukhtar SA, McAllister IL, et al. Inherited retinal diseases are the most common cause of blindness in the working-age population in Australia. Ophthalmic Genet 2021:1-9.

- Liew G, Michaelides M, Bunce C. A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16-64 years), 1999-2000 with 2009-2010. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004015.

- Pierrottet CO, Zuntini M, Digiuni M, et al. Syndromic and non-syndromic forms of retinitis pigmentosa: a comprehensive Italian clinical and molecular study reveals new mutations. Genet Mol Res 2014;13(4):8815-33.

- Stiff HA, Sloan-Heggen CM, Ko A, et al. Is it Usher syndrome? Collaborative diagnosis and molecular genetics of patients with visual impairment and hearing loss. Ophthalmic Genet 2020;41(2):151-8.

- Daiger SP, Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ. RetNet: Retinal Information Network. In: The University of Texas-Houston Health Science Center, ed. https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/ 2021.

- Vezinaw CM, Fishman GA, McAnany JJ. Visual Impairment in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Retina 2020;40(8):1630-3.

- Russell S, Bennett J, Wellman JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65 -mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2017;390(10097):849-60.

- Schwartz SG, Wang X, Chavis P, et al. Vitamin A and fish oils for preventing the progression of retinitis pigmentosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;6:CD008428.

Tools Designed for Healthier Eyes

Explore our specifically designed products and services backed by eye health professionals to help keep your children safe online and their eyes healthy.