Microbial Keratitis

Microbial keratitis – Written by Dr. Danielle Cadieux, MBBS, MHPE and Dr. Elsie Chan, B.Sc(Med) Hons, MBBS(Hons), MPH, FRANZCO.

What is microbial keratitis?

Microbial keratitis is an infection of the cornea (clear front dome of the eye that focuses light entering the eye). It is a sight-threatening condition caused by bacteria, fungi, or less commonly, other microbes (also called microorganisms). Loss of vision can be a consequence of the infection itself, or from longer-term complications such as corneal scarring. Therefore, it is crucial to diagnose and treat microbial keratitis quickly and effectively.

The following sections will briefly outline the global problem of microbial keratitis, what causes microbial keratitis, its signs and symptoms and some insights into its management and treatment.

The global problem of microbial keratitis

Data suggests that microbial keratitis exceeds 2 million cases per year worldwide with high numbers from developing regions, particularly in South, South East and East Asia. In the developed world, the estimated incidence is lower and ranges from 6.3 to 40.3 cases per 100,000 persons [1].

How does microbial keratitis develop?

Microbes are naturally present in the environment. They live in water, soil and on everyday surfaces, as well as on human skin and inside human bodies. Normally, the eye has natural barriers, such as the corneal epithelium (surface layer of the cornea), which prevents microbes from entering the cornea. Microbial keratitis occurs when the natural barriers are compromised, providing a way for microbes to enter the cornea and cause an infection.

Categories of microbial keratitis

Microbial keratitis can be categorized according to the cause of the infection. It is difficult to distinguish the different causes based solely on its appearance.

Bacterial keratitis

Bacteria are the main cause of microbial keratitis. There are many different bacteria that can infect the cornea. These include Staphylococci species (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus), Streptococcus species (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Staphylococci species commonly live on the human skin, in the throat and mouth. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is found in soil and water and is common in cases of contact-lens related bacterial keratitis.

Fungal Keratitis

Fungi are a less common cause of microbial keratitis, accounting for about 5 to 40% of cases. Fungal keratitis occurs more frequently in tropical and sub-tropical climates. Fungal keratitis is much more difficult to treat than bacterial keratitis.

What are the risk factors for developing microbial keratitis?

Risk factors for developing microbial keratitis include [2-4]:

- Geographic location – more common in tropical and subtropical climates due to higher sunlight exposure

- Contact lens use – the risk is higher with extended-wear contact lenses and sleeping in contact lenses

- Trauma to the cornea

- Underlying corneal diseases – e.g. severe dry eyes

- Previous eye surgery

- Eyelid abnormalities

- Long term use of steroid eye drops

- Underlying medical conditions causing a weakened immune system

What are the common signs and symptoms of microbial keratitis?

Signs and symptoms of microbial keratitis include:

- Redness

- Pain or irritation

- Tearing or discharge

- Blurred or decreased vision

- Sensitivity to light

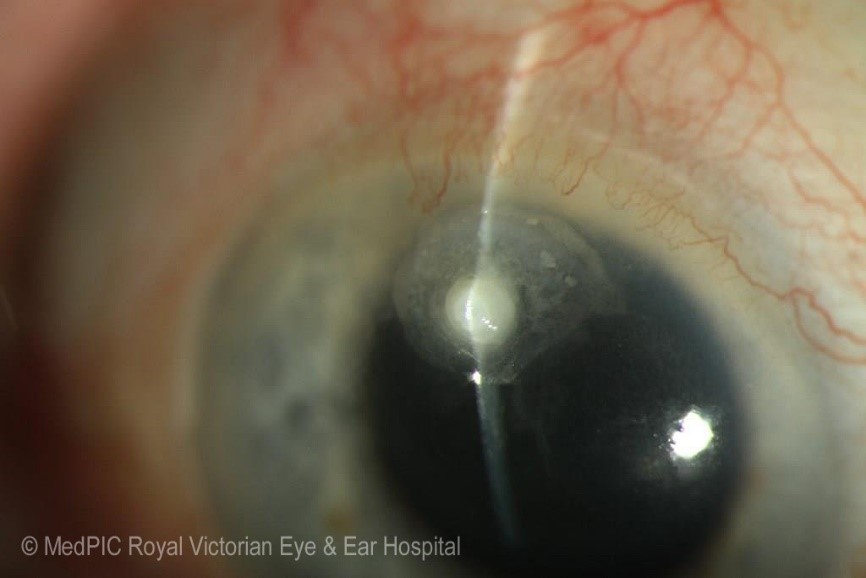

- A white spot on the cornea (called an infiltrate)

If you experience any of these symptoms and signs, schedule an appointment with an eye health professional to get your eyes checked. It is also important to note that the development of eye conditions may even start before symptoms appear, which makes going for regular and timely eye checks that much more essential.

How is microbial keratitis diagnosed?

Microbial keratitis is diagnosed based on history and a comprehensive eye examination by an eye health professional. A specialized microscope called a slit lamp is used to examine the cornea in detail. When a white or yellow area on the cornea is identified it is called an infiltrate. During the eye examination, a drop of an orange stain called fluorescein is used to identify the presence of a defect (ulcer) in the corneal epithelium. Fluorescein lines the ulcer and is seen as a bright green patch on the cornea when a blue light (called cobalt blue) illuminates the cornea.

How does an eye health professional confirm the cause of the microbial keratitis?

As it is usually not possible to distinguish the different causes (bacterial, fungal or other microbes) based only on the appearance of the infection, a swab of the eye, or a corneal ‘scraping’ may be required to identify the cause especially if the infection is large, affecting vision, or is not responding to treatment. The swab or scrape is performed following instillation of an anaesthetic eye drop to numb the surface of the eye. It involves using a cotton swab or tiny tools to remove a small sample from the infected area of the cornea. This is sent to a laboratory for specialised testing and examination for the microbe, and to test for the most suitable treatment.

Treatment for microbial keratitis

Microbial keratitis is treated with frequent application of antibiotic (for bacterial keratitis) or antifungal (for fungal keratitis) eyedrops. When severe, eye drops may be required every hour throughout the day and night. Microbial keratitis requires frequent follow-up to ensure response to treatment. In very severe cases where there is a high risk of a complication, a hospital stay may also be needed. Once improvement is seen, the frequency of eyedrops is decreased. Eye drops are typically required for 1 to 2 weeks for minor cases of bacterial keratitis. For cases of fungal keratitis, treatment for up to 6 months may be required. If worn, contact lens use must stop immediately. The eye should not be patched when microbial keratitis is present.

When a microbial keratitis fails to respond to treatment, the eye drops may be changed. In severe cases that fail to improve with eye drops, surgery may be required to control the infection and prevent it from spreading to other parts of the eye.

The infection has healed once the white infiltrate has settled, and the epithelium (surface layer of the cornea) has healed.

Complications of microbial keratitis

In the short term, microbial keratitis can cause pain, vision loss, or a full thickness breach of the cornea (a corneal perforation). A corneal perforation is a very serious, sight-threatening complication that may require urgent surgery.

Once the infection has healed, a white scar usually forms. Depending on the location and extent of this scar, it may cause a permanent reduction in vision, or may increase the dependence on glasses to see more clearly.

Can I prevent microbial keratitis?

Microbial keratitis can be prevented by managing the risks that can lead to infection. For example, if there is a history of an underlying eyelid disorder, then the eyelid disorder should be treated to prevent infection. For people who wear contact lenses, the risk can be minimised (although it is not eliminated) by using daily disposable contact lenses and improving contact lens care.

Appropriate contact lens care includes the following:

- Wash and dry hands thoroughly before handling contact lenses

- Follow the recommended contact lens replacement schedule

- Use fresh solution to clean and store contact lenses

- Do not use tap water to clean or store contact lenses

- Do not sleep in contact lenses

- Do not shower, swim or go in a hot tub while wearing contact lenses

For people who develop microbial keratitis following contact lens wear, it is strongly recommended that they see their optometrist or contact lens practitioner for advice to minimize future infections.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References:

- L. Ung, P. J. M. Bispo, S.S. Shanbhag, M. S. Gilmore, and J. Chodosh, “The persistent dilemma of microbial keratitis: Global burden, diagnosis, and antimicrobial resistance.” Surv Ophthalmol, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 255-271, May-Jun 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.12.003.

- F. Stapleton, and N. Carnt, “Contact lens-related microbial keratitis: how have epidemiology and genetics helped us with pathogenesis and prophylaxis.” Eye, vol. 26, pp. 185–193, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2011.288.

- M. Green, A. Apel, and F. Stapleton, “Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis.” Cornea, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 22-7, Jan 2008, doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318156caf2.

- L. Keay, K. Edwards, T. Naduvilath, H. R. Taylor, G. R. Snibson, K. Forde, and F. Stapleton, “Microbial keratitis predisposing factors and morbidity.” Ophthalmology, vol. 113, no. 1, pp. 109-116, Jan 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.08.013.

Tools Designed for Healthier Eyes

Explore our specifically designed products and services backed by eye health professionals to help keep your children safe online and their eyes healthy.