Nystagmus

Nystagmus – Written by A/Prof Larry Abel, BSc, MSc, Ph.D.

What is nystagmus?

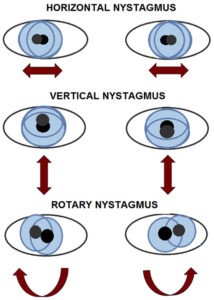

Nystagmus is an uncontrollable oscillation or movement of the eyes which begins with a slow movement. The eyes return to the point of fixation either with a rapid movement, or another slow movement. While usually horizontal, it can also be vertical, diagonal or circular, also referred to as rotary.

Nystagmus can be divided into two broad categories, early onset and acquired. Acquired nystagmus can arise from a multitude of causes [1]. The underlying problem can lie in numerous parts of the nervous system, with consequences ranging from self-limiting and minor to potentially lethal [2].

The following sections will briefly outline the global problem of nystagmus, the different types of nystagmus, and some insights into its treatment options.

The global problem of nystagmus

As many people have probably never heard of nystagmus, it might be thought to be very rare, but this isn’t the case; one detailed study found an overall prevalence of all forms of nystagmus to be 24 per 10,000 individuals [3]. Since acquired nystagmus is associated with such a broad range of underlying conditions, it will not be discussed in detail in this overview and rather, the focus will be on infantile forms of nystagmus, including those features that distinguish it from acquired nystagmus.

Types of nystagmus

Nystagmus arising in infancy

There are two main forms of nystagmus that begin within the first few months of life. These are infantile nystagmus syndrome (INS) and fusion maldevelopment nystagmus syndrome (FMNS). While eye movement recording can provide a definitive diagnosis, careful observation and history taking (eye care professional asking routine questions during an eye check) can most often distinguish between them. They can also usually identify who should be sent for further evaluation to rule out an acquired nystagmus.

Infantile nystagmus syndrome

Infantile nystagmus syndrome (INS), was formerly known as “congenital nystagmus” but the name was changed because it rarely begins literally at birth [4]. There are symptoms and clinical signs that can be valuable in identifying who may require timely referral.

In children, nystagmus is most commonly one of the congenital forms, sometimes associated with disorders of the retina (light sensitive tissue at the back of the eye) [5], [6]. The prevalence of acquired nystagmus rose from 17% in children to 40% in adults [5] and the onset in the first few months of life.

Signs and symptoms of infancy nystagmus syndrome

- Movement is horizontal and remains so in all gaze directions

- Often lessens at near and/or a particular gaze angle

- May intensify with stress, illness or effort to see something of interest

- Seeing the world move (oscillopsia) rare but may occur occasionally

- May reverse in direction with covering of one eye (i.e., show a latent shift)

- Headshaking may also be present

If you experience any of these signs and symptoms, schedule an appointment with an eye health professional to get your eyes checked. It is also important to note that the development of eye conditions may even start before symptoms appear, which makes going for regular and timely eye checks that much more essential.

It is most often seen in conjunction with eye problems such as albinism, congenital cataract, genetic retinal disorders, underdevelopment of the fovea (the high-resolution part of the retina) or it may also occur on its own. A number of INS related genes have been identified [5], [7]. Some of the features of INS are shared with other forms of nystagmus in infancy (e.g., FMNS with reversal upon covering an eye) but they separate INS and FMNS from acquired nystagmus.

The following video clip from Neuro Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library (NOVEL) shows a young man with a history of INS, who demonstrates a brisk nystagmus with the fast movement to the right in all positions of gaze except the far left, where it lessens and beats the other way when he looks more leftward. The video also demonstrates his nystagmus damping at near fixation. The left gaze null induces him to turn his face to the right, as can be seen at the beginning of the video.

Seeing nystagmus remain horizontal in both up and downgaze are important indicators of an early onset nystagmus, rather than an acquired form.

Fusion maldevelopment nystagmus syndrome

This was previously known as latent-manifest latent nystagmus (LMLN). A latent nystagmus is one present only when an eye is covered, with the fast phase beating towards the viewing eye [8]. It is almost always seen with strabismus (a turned eye). In contrast, INS may or may not coexist with a turned eye [8].

If both the turned and straight eye are uncovered, the nystagmus beats towards the eye looking at the target. This property led to the paradoxical term “manifest latent nystagmus” or MLN, first attributed to Kestenbaum [9]. The MLN may be so small as to be almost undetectable without recording.

INS reversing upon covering an eye is called a “latent shift.” INS with a latent shift and FMNS look similar clinically, so eye movement recoding may be the only way to distinguish between them. However, the reversal with occlusion distinguishes these two early onset forms of nystagmus from acquired nystagmus. A video clip by Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library, University of Utah demonstrates latent nystagmus.

Besides the association with strabismus, another feature of FMNS is the absence of a null position of gaze, rather, FMNS increases as the patient looks in the direction of the fast phase.

Acquired nystagmus

As the causes of acquired nystagmus are many and varied, they won’t be dwelt upon here, but there are some key features of nystagmus that should prompt medical attention:

- Onset (not simply detection) after the 1st few months of life

- Constantly seeing the world move when it isn’t (oscillopsia)

- Direction of motion other than horizontal

- Different motion in the two eyes

- An association with dizziness

- Changes associated with posture (rolling over in bed, bending down, etc.)

We won’t discuss acquired nystagmus further other than to note that while many types are self-limiting and don’t persist, medical attention should be sought. Some good references on acquired nystagmus are available [1], [2], [10], [11].

Treatment of nystagmus arising in infancy

Persons with INS may be told that there is nothing to be done for the condition. This isn’t true. For INS, no treatment will make the nystagmus disappear completely. However, there are a range of possible options to maximise vision and minimise the problems arising from the condition. Some are optical, some surgical and some medical. But what do we mean by saying “maximise vision” with INS improvements include:

- Better visual acuity—the ability to resolve the smallest possible objects

- Best possible acuity over as wide a range of gaze angles as possible

- Speed of “seeing”—some people with INS need more time to see

- Improved appearance—the eyes wiggle less obviously, face turn is minimised

Some treatments address more of these aspects of vision than others. We’ll now consider the interventions currently used clinically.

Optical management

This might seem obvious but in the face of wiggling eyes, sometimes correcting refractive errors such as myopia (near sightedness), hypermetropia (far sightedness) or astigmatism is neglected.

Even when the eyes are moving and have structural problems, it is still important to provide them with the clearest possible image [12]. This can be done with spectacles or contact lenses.

There is some evidence that contacts also improve the nystagmus itself [13] but there are also studies to the contrary [14]. When there is a null location not too far from straight ahead, prism lenses can be used to shift the image in the beneficial direction [15]. A null seen when viewing near objects can be used by placing prism lenses with their bases facing outwards, forcing the eyes to turn inwards to view distant targets [16], [17].

Surgical management

Surgery for nystagmus dates back to the mid-1950s [9], [18]. The mainstay procedure still widely used when patients turn their face to use a null location involves measuring the affected person’s face turn, then repositioning and shortening the horizontal eye muscles to rotate the eyes in their orbits by that amount in the opposite direction.

Early recording studies also observed that this not only shifted the null but broadened it [19]. Widening and centring the null both addresses the cosmetic and orthopaedic issues caused by face turns but also provides a broader range of eye positions where vision is as good as it can be.

When the null is at near, the eye muscles facing the nose can be weakened, so that the signal to them that previously turned the eyes inwards now brings them facing straight [20]. When nulls both to the side and at near are present the surgeries can be combined, often giving even better results [21].

Although FMNS may not be problematic when both eyes are open [22], there are cases where symptoms of the manifest nystagmus (i.e., that seen when both eyes are viewing) are bothersome. It has been shown that if the two eyes are aligned and binocular vision (ability of both eyes to work together in sync) restored early enough that the manifest nystagmus can be abolished [23].

Medical management

While certain forms of acquired nystagmus can be greatly minimised with medication [1], efforts to reduce INS have been less successful. Improvements have been described with some drugs repurposed from neurology [24], [25]. Small studies have also noted improvements with eye drops, again originally used for other conditions [26], [27]. While promising, improvements are modest and must be balanced against the issues involved in taking a medication for a lifetime.

Social management

While not a treatment for nystagmus per se, dealing with the social consequences of nystagmus is important, as social issues are surprisingly significant [28]. The effects on appearance can be problematic, particularly in cultures where eye contact is valued. A face turn can elicit bullying amongst children or accusations of cheating from teachers.

Institutions generally are unfamiliar with a condition where at times vision may be fairly good but also variable and in which individuals need longer to see things. These issues arise at all levels, from school to university to workplaces. The social impacts are not strongly associated with reduced visual acuity but rather with other aspects of the condition [29].

Along with focusing on vision related challenges with nystagmus, the significance of social related impacts must be appreciated and addressed. Patient-led groups such as the Nystagmus Network UK and the American Nystagmus Network offer valuable resources to those with nystagmus and their parents or carers.

Summary of nystagmus

Nystagmus arising in early infancy can present a range of problems, related to visual acuity, speed of visual processing and variability with gaze or internal state. A range of treatments is available but virtually none are curative; however, with proper management, problems can be minimised.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, include but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health care provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References:

- J. C. Rucker, “An Update on Acquired Nystagmus,” Semin. Ophthalmol., vol. 23, pp. 91–97, 2008.

- L. S. Ediriwickrema, “Acquired Nystagmus :,” Adv. Ophthalmol. Optom., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 339–354, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.yaoo.2017.04.001.

- N. Sarvananthan et al., “The prevalence of nystagmus: the Leicestershire nystagmus survey,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., vol. 50, pp. 5201–5206, 2009.

- W. G. CEMAS, “A National Eye Institute Sponsored Workshop and Publication on The Classification Of Eye Movement Abnormalities and Strabismus (CEMAS)..” National Eye Institute, The National Institutes of Health, 2001.

- O. Ehrt, “Infantile and acquired nystagmus in childhood,” Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 567–572, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2012.02.010.

- D. L. Nash, N. N. Diehl, and B. G. Mohney, “Incidence and Types of Pediatric Nystagmus,” Am. J. Ophthalmol., vol. 182, pp. 31–34, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.07.006.

- E. Papageorgiou, R. J. McLean, and I. Gottlob, “Nystagmus in childhood,” Pediatr Neonatol, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 341–351, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.02.007.

- L. F. Dell’osso, S. Traccis, and L. A. Abel, “Strabismus – a necessary condition for latent and manifest latent nystagmus,” Neuro-Ophthalmology, vol. 3, no. 4, 1983, doi: 10.3109/01658108308997312.

- A. Kestenbaum, Clinical methods of neuro-ophthalmologic examination, 2nd ed. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1961.

- A. G. Lee and P. W. Brazis, “Localizing forms of nystagmus: symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment,” Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep., vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 414–420, 2006.

- L. F. Dell’Osso and Z. I. Wang, “Extraocular proprioception and new treatments for infantile nystagmus syndrome,” Prog Brain Res, vol. 171, pp. 67–75, 2008, doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)00610-9.

- R. W. Hertle, “Examination and refractive management of patients with nystagmus,” Surv. Ophthalmol., vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 215–222, 2000, doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00153-3.

- L. F. Dell’Osso, S. Traccis, L. A. Abel, and S. I. Erzurum, “Contact lenses and congenital nystagmus,” Clin. Vis. Sci., vol. 3, no. 3, 1988.

- V. Biousse et al., “The use of contact lenses to treat visually symptomatic congenital nystagmus,” J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, vol. 75, pp. 314–316, 2004.

- L. F. Dell’Osso, G. Gauthier, G. Liberman, and L. Stark, “Eye movement recordings as a diagnostic tool in a case of congenital nystagmus,” Am. J. Optom. Arch. Am. Acad. Optom., vol. 49, pp. 3–13, 1972.

- M. J. Thurtell and R. J. Leigh, “Therapy for nystagmus,” J Neuroophthalmol, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 361–371, 2010, doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181e7518f.

- M. Graf, “Kestenbaum and artificial divergence surgery for abnormal head turn secondary to nystagmus. Specific and nonspecific effects of artificial divergence,” Strabismus, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 69–74, 2002.

- J. R. Anderson, “Causes and treatment of congenital eccentric nystagmus,” Br. J. Ophthalmol., vol. 37, pp. 267–281, 1953.

- J. T. Flynn and L. F. Dell’Osso, “The effects of congenital nystagmus surgery,” Ophthalmology, vol. 86, no. 8, pp. 1414–1427, 1979.

- A. Spielmann, “Clinical rationale for manifest congenital nystagmus surgery,” J. Am. Acad. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Stribismus, vol. 4, pp. 67–74, 2000.

- A. A. Zubcov, N. Stark, A. Weber, S. S. Wizov, and R. D. Reinecke, “Improvement of visual acuity after surgery for nystagmus,” Ophthalmology, vol. 100, no. 10, pp. 1488–1497, 1993.

- J. Lee, “Surgical management of nystagmus,” J R Soc Med, vol. 95, no. 5, pp. 238–241, 2002.

- A. A. Zubcov, R. D. Reinecke, I. Gottlob, D. R. Manley, and J. H. Calhoun, “Treatment of manifest latent nystagmus,” Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 110, pp. 160–167, 1990.

- R. McLean, F. A. Proudlock, S. Thomas, C. Degg, and I. Gottlob, “Congenital nystagmus: randomized, controlled, double-masked trial of memantine/gabapentin,” Ann. Neurol., vol. 61, pp. 130–138, 2007.

- E. Papageorgiou, K. Lazari, and I. Gottlob, “The challenges faced by clinicians diagnosing and treating infantile nystagmus Part II: treatment,” Expert Rev. Ophthalmol., no. August, 2021, doi: 10.1080/17469899.2021.1970533.

- R. W. Hertle, D. Yang, T. Adkinson, and M. Reed, “Topical brinzolamide (Azopt) versus placebo in the treatment of infantile nystagmus syndrome (INS),” Br. J. Ophthalmol., vol. 99, no. 4, pp. 471–476, 2015, doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305915.

- L. F. Dell’Osso, R. W. Hertle, R. J. Leigh, J. B. Jacobs, S. King, and S. Yaniglos, “Effects of topical brinzolamide on infantile nystagmus syndrome waveforms: Eyedrops for nystagmus,” J. Neuro-Ophthalmology, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 228–233, 2011, doi: 10.1097/wno.0b013e3182236427.

- R. J. McLean, G. D. E. Maconachie, I. Gottlob, and J. Maltby, “The Development of a Nystagmus-Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire,” Ophthalmology, vol. 123, no. 9, pp. 2023–2027, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.05.033.

- A. Das et al., “Visual functioning in adults with Idiopathic Infantile Nystagmus Syndrome (IINS),” Strabismus, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 203–209, 2018, doi: 10.1080/09273972.2018.1526958.

Tools Designed for Healthier Eyes

Explore our specifically designed products and services backed by eye health professionals to help keep your children safe online and their eyes healthy.